Many commentators argue that the 21st century belongs to the novel, pointing to its dominance in publishing, bestseller lists, and critical discourse. The novel is often described as a uniquely social form, tracing individual experience within capitalist modernity, as Franco Moretti suggests. Others, such as Pascale Casanova, emphasize its role as the privileged vehicle of international literary circulation, traveling widely and accruing cultural capital across the globe. These perspectives suggest that the novel now defines how we understand the contemporary world.

But is this emphasis justified? Does the rise of the novel eclipse other literary forms, such as poetry? And what does this mean for literature’s ability to reflect and challenge our social and political realities?

From the market’s point of view, the novel is clearly ascendant: readers demand expansive narratives; publishers invest heavily; and translation networks extend its reach. Poetry, by contrast, has been pushed to the margins, compressed into Instagram snippets or treated as a boutique art.

Yet the central question persists: why do we instinctively call this the age of fiction, and what does that mean for literature’s power to interrogate our existence?

—

The dominance of the novel invites scrutiny. Does it truly serve the needs of our time? And what is lost when poetry is relegated to the sidelines?

The Hungarian critic Georg Lukács once suggested that the novel is the form of a world abandoned by God. Unlike the epic, where meaning is cosmically assured, the novel emerges from a landscape where meaning must be wrestled from disenchanted social life. That insight has not lost its force.

Our present, marked by global precarity, ecological crisis, and the fragmentation of communities, remains a world without guarantees. The novel, sprawling and adaptable, offers one way of drawing coherence from such fragmentation.

Part of its power lies in scale. A novel can extend over hundreds of pages, encompassing families and cities, even civilizations, while tracing the subtle intersections between the intimate and the structural. A war can enter a kitchen; an economy can fray a marriage; a migration can unsettle an identity. The modern novel, from Dickens to Adichie, thrives on precisely these entanglements.

—

Adaptability is also central to the novel’s strength. The critic Mikhail Bakhtin saw the novel not simply as one genre among others but as a heteroglossia—a vessel for multiple voices and discourses.

In a world where boundaries blur, the novel endures because it can absorb diverse forms, from reportage and memoir to autofiction, science fiction, and philosophy. Poetry, by contrast, often preserves its density and autonomy, resisting such absorption.

This raises a question: does the novel’s expansiveness risk diluting critique? To describe the world in detail is also to risk normalizing it, making structures of violence appear inevitable rather than intolerable. Here, poetry’s counter-presence becomes indispensable.

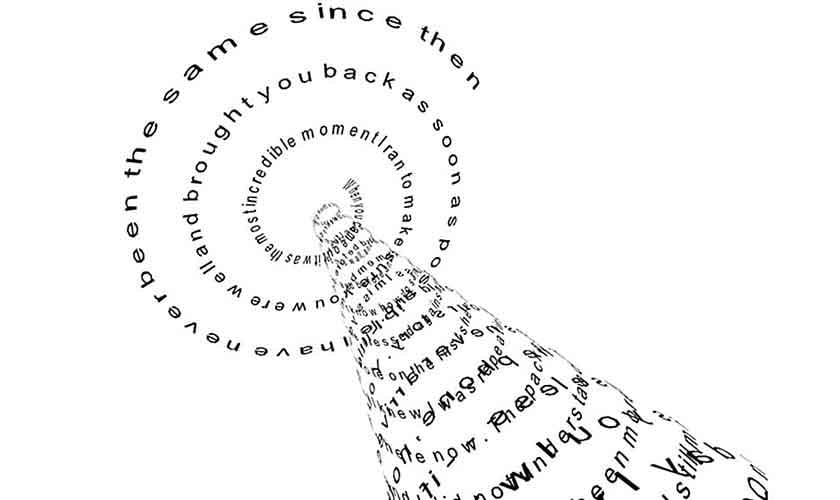

If the novel immerses, poetry interrupts. It cuts; and often wounds.

—

The Polish poet Wisława Szymborska once remarked that whatever inspiration is, it’s born from a continuous “I don’t know.” That refusal to narrativize, to impose coherence, is precisely poetry’s strength. It insists on fracture, ambiguity, and resistance.

Historically, poetry has been the idiom of protest. From Shelley’s claim that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world to Mahmoud Darwish’s lyrical defiance, poetry has crystallized dissent in ways the novel rarely does.

Protest slogans, chants, and graffiti all rely on poetic compression. When revolutions seek a voice, they do not turn to 500-page novels but to a handful of lines.

—

Why, then, is poetry so often marginalized today?

One reason is economic: novels sell, poetry does not. Another is linguistic: as Octavio Paz observed, poetry is untranslatable; only another poem can be a true translation. Translation risks flattening rhythm and ambiguity, making global circulation difficult.

A third reason is cultural: in an age of bingeable stories, the novel seems serious because it mirrors the narrative modes already dominant in television and streaming. Poetry’s brevity, paradoxically, counts against it.

Yet, as Ben Lerner notes in *The Hatred of Poetry*, the very impossibility of poetry—its resistance to market norms and easy consumption—is what gives it purpose. A poem’s compressed impact stands in stark contrast to the novel’s expansiveness, allowing its political urgency to remain vital.

—

The rise of translation has further entrenched the novel’s dominance. As David Damrosch and other world literature scholars argue, translation is not merely about crossing languages but about shaping canons.

The books that circulate globally become the books that matter—and those books are overwhelmingly novels. A novel can be marketed as a cultural window. Elena Ferrante’s *Neapolitan Quartet* is not simply Italian fiction but Italy itself, packaged and exported. Han Kang’s *The Vegetarian* is both a story of alienation and a synecdoche for South Korean modernity.

Publishers, consciously or otherwise, sell novels as cultural ambassadors. Poetry resists this logic. Its rhythms, its play of sound, its ambiguities are harder to sell as a window into a nation. Translation can betray poetry more profoundly than prose, and publishers shy away from the risk.

The result is a global marketplace filled with novels but starved of poems. We can read fiction from everywhere, yet our poetic horizons remain strikingly provincial.

—

One cannot discuss literature today without acknowledging the role of algorithms. Amazon’s recommendation engine, Goodreads ratings, and TikTok’s BookTok trends are now as influential as critics or prizes.

Novels lend themselves easily to this ecosystem: they can be serialized, hyped, and reviewed at length. Their narratives fit the rhythms of binge culture. Poetry, by contrast, enters this world in fragments.

Instagram poetry, epitomized by Rupi Kaur, shows the form’s adaptability—but also its flattening. As critic Stephanie Burt has noted, such poetry often collapses into content: digestible affirmation rather than linguistic experimentation.

Meanwhile, politically scathing or formally complex poetry survives largely in small presses, far from the reach of algorithmic visibility.

—

If the novel dominates today, it may be less because of any innate capacity to portray social and political existence and more because of its compatibility with capitalist and algorithmic circulation.

Literary forms are being reshaped not only by aesthetic needs but also by the infrastructures of visibility.

—

What will future historians say of our literary age?

Franco Moretti, with his charts and graphs, might reduce it to patterns of circulation: the global novel ascendant, poetry in retreat. Pascale Casanova could emphasize the geopolitics of translation, the Greenwich meridian of Paris or New York dictating what counts as literature.

Others may highlight the rise of autofiction—Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, Annie Ernaux—as evidence that the boundaries of fiction itself are being reconfigured.

Yet the story could also be told differently. This may be remembered not only as the great age of the novel but as the moment when poetry, though marginal in visibility, re-emerged in times of crisis as the sharpest voice of resistance.

Wars, revolutions, and climate breakdowns may well restore poetry’s urgency.

—

Literary forms never remain static. They rise and fall with history’s demands.

To say that we live in an era of fiction captures the novel’s global dominance, reinforced by translation, prizes, and algorithms. Yet this focus risks obscuring the fact that poetry remains vital to literature’s role in society.

The rise of the novel is driven as much by economic and technological forces as by literary merit, prompting us to ask what we truly gain and what we lose in privileging narrative forms.

—

Perhaps it is more accurate to say that we live in an era of narrative. Stories in novels, streaming series, and podcasts dominate cultural attention. The novel is literature’s contribution to this hunger.

Poetry, in contrast, offers not narrative but rupture. It interrupts, resists, refuses.

The future of literature lies in the tension between novel and poem: immersion versus incision, sprawl versus shard, world-building versus disruption.

The novel reflects and shapes the contours of our present, but poetry remains an urgent counterpoint. Literature’s greatest strength may come from holding the two together: expansive stories alongside sharp moments of rupture that speak to enduring truths.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1348312-shapes-of-our-present